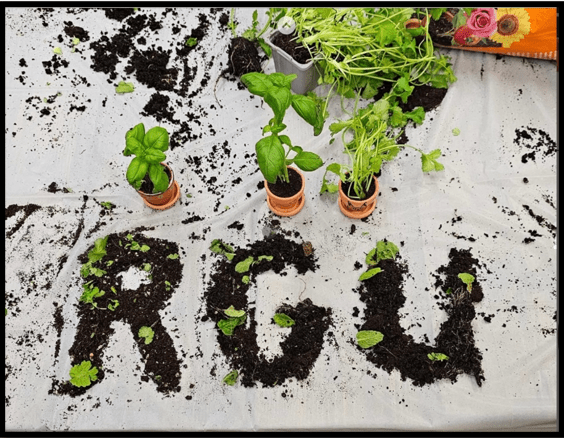

Studying Public Health and Health Promotion at RGU

After working as a pharmacist in Ghana, Adanna Blessing chose to move to Aberdeen to study a master’s in Public Health and Health Promotion to be better equipped to advocate for women and children’s health. She shares her experience as a student, from the learning […]

Student

Top tips to finding accommodation in Aberdeen as a student

With the academic year coming to an end for many students, it will now be time to pack up and find somewhere new to live in September if you are going back to university. RGU ResLife shared with us five top tips to finding accommodation […]

Student

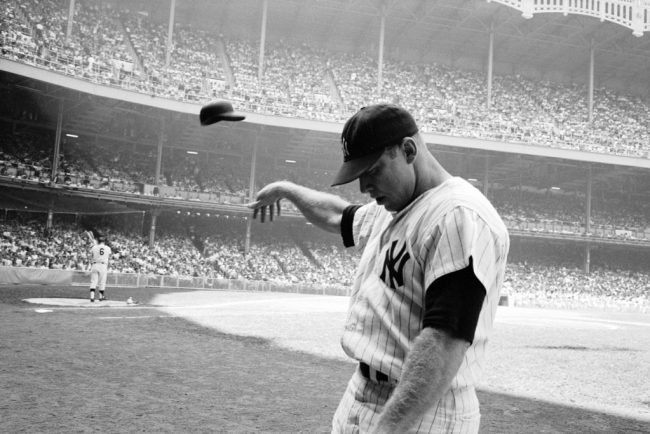

Twilight of an Idol: A Portrait of Mickey Mantle in Decline

The greater the athlete, the tougher it is to leave the arena. It was certainly the case for Yankees center fielder Mickey Mantle. A tremendous natural talent, Mantle became a dominant force on the diamond almost as soon as he joined the Yankees in 1951. […]

People

Studying an MBA online at RGU while working full-time

MBA graduate Fiona shares her experience studying online at RGU and juggling university with a full-time job and new-born. My background Hi I’m Fiona, I live in Aberdeenshire and work in integrity monitoring in the oil and gas industry and have undertaken various science-based roles […]

StudentMBA graduate Fiona shares her experience studying online at RGU and juggling university with a full-time job and new-born.

My background

Hi I’m Fiona, I live in Aberdeenshire and work in integrity monitoring in the oil and gas industry and have undertaken various science-based roles from lab work, offices, to rotational offshore shifts, since graduating from my first degree at Robert Gordon University in Forensic Science with Chemistry in 2010.

I wanted to learn more about business management and submitted an application to study at RGU for the part-time, online MBA course which was successful. I then joined the cohort in September 2022.

My experience studying flexibly online

The course lectures were held in the evening, which allowed me to log on after finishing work. The course being online-based gave the flexibility to watch the lectures at a later time that was more suitable on occasions when I could not join the live sessions, as the presentations were uploaded onto the university portal.

The coursework dates were mentioned early in the semester to allow students to plan ahead and meet the submission deadline. During the second semester, I became pregnant and juggled the end of the course with a new-born which was challenging at times.

The highlight of the MBA course was meeting the RGU lecturers and fellow students in person during Leadership Week who travelled lengthy distances to be in Aberdeen for the occasion. This was an intense week in which I learned a lot from the lectures, guest speakers, group work and business simulation.

The final consultant project was also a highlight of the degree which allowed me to contribute to my employer with a research project by guidance from an RGU project supervisor. Once this was completed, I presented my project to my colleagues. It was great to share my research and put it into practice.

Finally, the graduation was a great sense of achievement to celebrate the completion of the degree with fellow students and my family. I now look forward to applying my learnings to my career.

Fiona Eyre

Related blogs

Doing an MBA or starting a family? I chose both!

The post Studying an MBA online at RGU while working full-time appeared first on RGU Student Blog.

From recruiting students in India to becoming one at RGU

International student Twinkle quit her job in student recruitment in India and moved to Aberdeen to study a master’s in Digital Marketing. She shares how her role recruiting students inspired her to go back to university and her experience adapting to life in Scotland. Life […]

StudentInternational student Twinkle quit her job in student recruitment in India and moved to Aberdeen to study a master’s in Digital Marketing. She shares how her role recruiting students inspired her to go back to university and her experience adapting to life in Scotland.

Life has an uncanny way of coming full circle. My journey from recruiting students in India to becoming a student myself has been one of the most profound and humbling experiences of my life. It’s a story of transitions, challenges, and the incredible growth that comes when you step out of your comfort zone. In this blog, I’ll take you through the highs and lows of this transformation, share real-time facts from my experiences, and reflect on what this journey has taught me.

My passion for education and guiding students started early in my career. As someone who has always believed in the power of education to transform lives, I found immense joy in helping students navigate their academic paths. I always had good communication and convincing skills, which I made the best use of in counselling and continuously upgrading my skills. For years, I worked as a Senior Admissions Counsellor, engaging with students and parents, addressing their concerns, and matching them with the right opportunities.

I helped countless students shape their futures, and the satisfaction of seeing them succeed was deeply fulfilling. However, along the way, I realized that I, too, longed for growth and new experiences. I wanted to step into the very world I had been advocating for—to become a student once again and gain a fresh perspective on higher education.

The beginning: My career path and recruiting students in India

My career began with a strong foundation in education. I completed my Bachelor of Computer Applications (BCA) in 2018, followed by an MBA in 2020. Soon after, I stepped into the professional world as a Senior Admissions Counsellor, recruiting students and guiding them through their educational journeys. This role demanded a deep understanding of young minds, the ability to empathize with their aspirations, and the skills to guide them toward their dreams. Each day, I worked with students and families navigating the maze of educational opportunities. It was both fulfilling and challenging.

I vividly remember the pride in a student’s eyes when they received an offer from their dream university, and the relief in parents’ faces when their child’s future felt secure. But it wasn’t always smooth sailing. Convincing students to step out of their comfort zones and helping families overcome financial and emotional hurdles were significant challenges. Still, the work was meaningful, and I loved being a part of their journey.

The turning point: Becoming a student

Despite the rewarding nature of my work, there was always a part of me that longed for personal growth—to experience the very journey I was advocating for. This inner calling led me to take a bold step: I decided to pursue higher studies myself.

Making this decision was not easy. Questions plagued me: Was I too late to go back to being a student? Could I adapt to the academic pressures and cultural shifts of studying abroad? Would I regret leaving a stable career? Ultimately, the desire to grow and learn won out over fear, and I embarked on this life-altering path.

Throughout this journey, I was fortunate to have the unwavering support of my parents, my boss and my managers. They not only motivated me but also stood by my decision, ensuring I never doubted myself. Their encouragement helped me choose MSc Digital Marketing—a flagship course in today’s digital-first world. Their belief in my potential played a pivotal role in helping me take this leap of faith.

Choosing MSc Digital Marketing as my career path felt natural. I have always been passionate about creating content, whether it was making social media posts, crafting engaging reels, or coming up with creative ideas. This interest in digital creativity made Digital Marketing an ideal subject for me, and I’m thrilled to have taken this step.

Why I chose RGU

Choosing Robert Gordon University (RGU) as my priority university felt personal from day one. The connection between RGU and my organization was always very strong, which made me choose RGU without any second thought. After spending three years recruiting students to RGU for their bachelor’s and master’s programmes, I had an in-depth understanding of the University’s values and offerings.

RGU consistently stands out for its high student satisfaction and excellent employment rates. I also received glowing feedback from previously recruited students who spoke highly of their experience at RGU. These factors, combined with my familiarity and trust in the institution, solidified my decision to join. It felt like a natural continuation of my journey.

Adding to this, I was also chosen to be a Student Ambassador for RGU, which gave me a wider space to be a part of the University and truly immerse myself in its culture. This was an incredibly prideful moment for me, as it allowed me to represent the University and help new students navigate their own journeys.

Living in Aberdeen: A dream come true

Aberdeen is a city where culture and sophistication meet, making it a truly unique place to live. Every day, I wake up to a beautiful new view of the city, and each day feels like a dream come true. The city’s charm lies in its blend of history, modernity, and stunning landscapes.

Aberdeen has its own distinct vibe—one that is warm and welcoming. The people here are incredibly kind and supportive, which has made my transition so much smoother. Walking through the quaint streets, exploring the coastline, and experiencing the vibrant student community have all made me feel at home. I am immensely grateful for choosing Aberdeen as the city to live in, as it has enriched my journey in ways I never imagined.

Back in India, I never thought I would experience my life’s first snowfall in the UK, and trust me, it was all worth it. My beautiful city was covered in snow, and every walk was mesmerizing. It felt like a dream to see Aberdeen draped in white, making my experience here even more magical.

Struggles and challenges faced

Transitioning from a recruiter to a student was humbling, to say the least. Suddenly, I was on the other side, grappling with the very uncertainties I had once helped others navigate.

Cultural Adjustments: Moving to a new country meant adapting to different customs, teaching styles, and social norms. It was both exciting and overwhelming.

Academic Pressure: The rigor of coursework, coupled with the need to excel, was a sharp contrast to my professional routine. Time management became a daily battle.

Emotional Hurdles: From missing home to questioning my decision during tough times, the emotional weight was significant. I often found myself reflecting on the students I had guided and gaining a newfound respect for their resilience.

Financial Management: Balancing tuition fees, living expenses, and part-time work added another layer of complexity to the journey.

Lessons learned along the way

Despite the struggles, this experience has been incredibly enriching. Here are some of the key lessons I’ve learned:

Empathy Deepened: Experiencing the challenges of being a student first-hand has made me more empathetic. I now understand, on a visceral level, the courage it takes to leave behind familiarity in pursuit of education.

Perspective Gained: Being a student again reminded me that learning is a continuous journey. It’s not just about acquiring knowledge but about personal growth and adaptability.

Humility and Resilience: The setbacks I faced taught me to stay grounded and persistent. Each obstacle became an opportunity to grow stronger.

Moments of joy

For all the challenges, there were countless moments of joy that made the journey worthwhile:

Building Friendships: I formed bonds with classmates from around the world, learning from their diverse experiences and perspectives.

Achieving Milestones: From acing difficult exams to completing projects, each accomplishment felt like a personal victory.

Personal Growth: The confidence I’ve gained through this journey is immeasurable. I’ve discovered strengths I didn’t know I had.

Reflections on the journey

Looking back, I’m filled with gratitude for the path I chose. Transitioning from a recruiter to a student has given me a unique dual perspective. I now see the education system through two lenses—as someone who once guided students and as someone who’s experienced their struggles firsthand.

If I could offer advice to anyone considering a similar path, it would be this: Embrace change. Growth happens when you challenge yourself, even when it’s uncomfortable. The courage to step out of your comfort zone can lead to some of the most rewarding experiences of your life.

Conclusion: The dual perspective

My journey has come full circle, and I wouldn’t have it any other way. Being both a recruiter and a student has given me insights I could never have gained otherwise. As I look toward the future, I’m excited to blend these experiences—to guide others with empathy and to continue learning with an open heart.

To anyone reading this: “Conquer your dreams” Keep chasing them, and don’t be afraid to reinvent yourself along the way. Life has a way of surprising you, often in the best ways possible.

Here’s signing off…

Twinkle

Related blogs

A Greek in Scotland studying Architecture at RGU

My journey from Canada to Aberdeen and RGU

Swapping the Baltic Sea for the North Sea – My hopes and fears

The post From recruiting students in India to becoming one at RGU appeared first on RGU Student Blog.

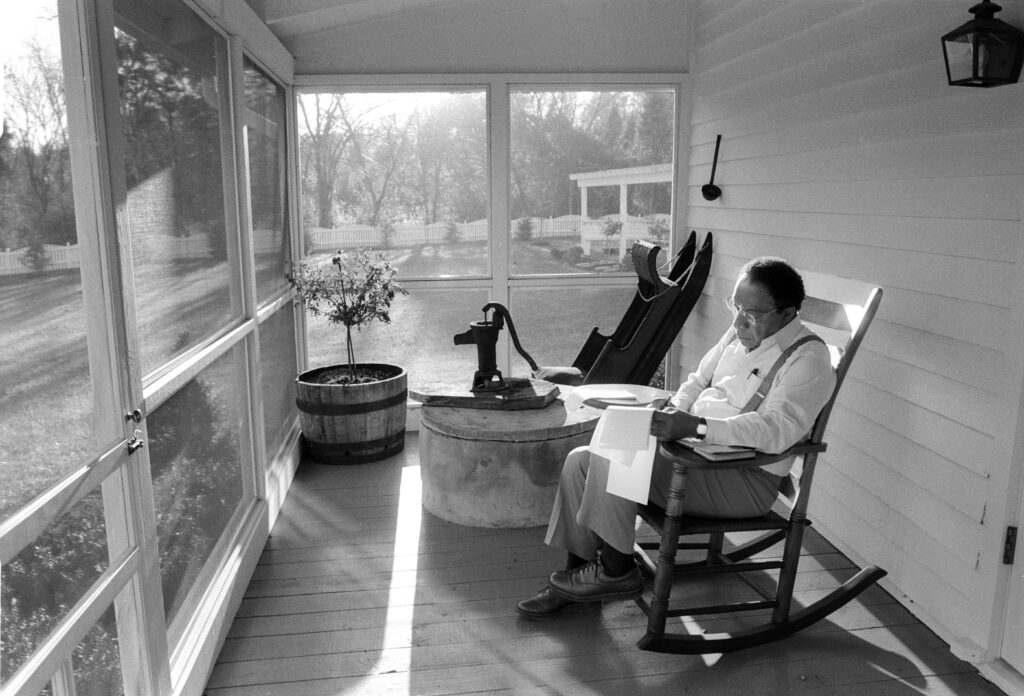

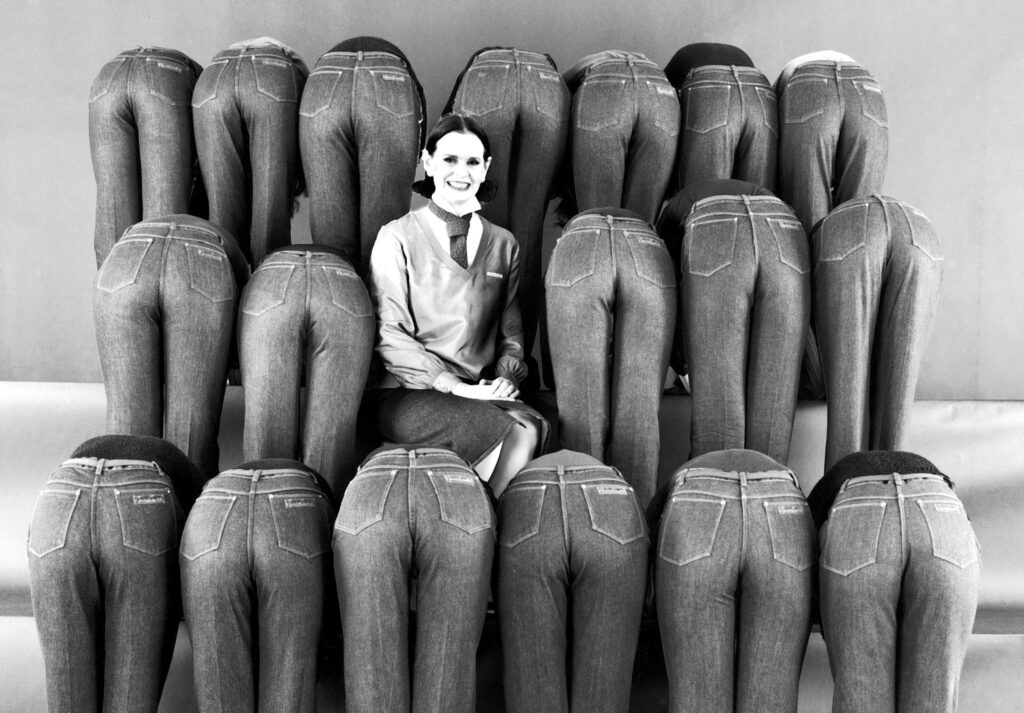

The Work of Evelyn Floret, a Master of Intimate Portraits

Evelyn Floret’s most outstanding trait as a photographer may well have been her ability to put her subjects at ease. She shot portraits for PEOPLE magazine from 1976 to ’96, and Floret says that the magazine often chose her for an assignment when they thought […]

PeopleEvelyn Floret’s most outstanding trait as a photographer may well have been her ability to put her subjects at ease. She shot portraits for PEOPLE magazine from 1976 to ’96, and Floret says that the magazine often chose her for an assignment when they thought the subject might need a photographer with a gentle touch. “I’m a sensitive person, I’m appreciative,” Floret says. “I’m not critical. I have a positive outlook and an appreciation for people, and that would translate into how I would behave on an assignment.”

Indeed, Floret’s subjects look like they are posing before someone who they believe appreciates them and will take care of them.

Floret may have been able to connect with her subjects, most of whom are creative types, because she is an artist herself. In addition to being a photographer, she practices other visual arts, most notably sculpture. She says her interest in sculpture was an outgrowth of her portrait photography .

And Floret came to photography with a rich life experience. She was born in Paris in 1936, and four years later she and her parents had to flee that city when Germany invaded France. After moving from town to town for a year, she and her family sailed from Portugal to the United States, settling in St. Louis in 1941. Her nationality remained in important part of her identity. During World War II her family would host weekly brunches for French soldiers stationed at nearby Scott Air Force Base, where radio operators and technicians were trained. After Floret graduated college, her first professional work was teaching French. It tells you much about her convivial personality that, all these decades later, she is still in touch with some of her former students.

Floret, deciding she wanted an artistic life, later moved to New York. She briefly attempted to become an actress before finding her calling in photography. A couple LIFE photographers played key roles along the way. One of her formative experiences was taking a class at the New School with Phillipe Halsman. and it was John Dominis who helped pave her entry into the magazine world while he was working at PEOPLE.

Soon she was shooting photos of all sorts of artists, from Lynda Carter to Margaret Atwood.

In more than a few of Floret’s photos, she had the stars pose with their pets. For example, actress Nancy Marchand, who at the time was on the television show Lou Grant and would go on to play Olivia Soprano in The Sopranos, held her dog up close to her face. “The animals brought the pictures to life because the people loved them so much,” Floret said. “That was the case with Nancy Marchand.”

Floret has been reflecting on her career lately because she is currently in the process of completing a book that compiles her favorite photographs from her years with the magazine. Looking at all the portraits she shot of such talented and accomplished people has filled her with appreciation and wonder.

“I just treasure the people that I photographed,” she says. “I am reliving the joy of the result of the experiences, and I feel appreciation for the generosity of the editors who gave the assignments, and the people who allowed me into their private lives to take these very personal photographs.”

Enjoy this selection of images from Floret that highight both the range of people she photographed and also the quality of her artistry.

Author Alex Haley writing as he sits in rocking chair on porch of house on his farm. Floret described Haley as “a treasure’ and said that she loved his quote, “If i knew what success would bring, I would have been typing faster.”

Courtesy of Evelyn Floret

Actress Nancy Marchand with her dog in 1982, when she was a regular on the television show “Lou Grant.”

Courtesy of Evelyn Floret

Gloria Vanderbilt in 1979. After trying shots with the models facing forward, photographer Evelyn Floret asked the models to turn around. “She was like a little flower with that pink satin blouse in the center of it all,” Floret said. “I knew i had the picture when i saw that.”

Courtesy of Evelyn Floret

Lynda Carter of Wonder Woman fame and Robert Altman enjoyed a picnic on the banks of the Potomac in 1983. They married in 1984, and remained together until his death in 2021. Floret says, “They were very much in love. It was a joy to be around them.”

Courtesy of Evelyn Floret

For a story on George Way, an expert antiques collector who also worked at a deli counter, Floret photographed him in the bed in which he sleeps, an Elizabeth I from 1571. At the time of the shoot, in 1991, the bed was valued at $400,000.

Courtesy of Evelyn Floret

Martha Stewart posed outside of her Connecticut home in 1987, when she had just come out with a book on wedding cakes.

Courtesy of Evelyn Floret

Martha Stewart in 1987. Floret described Stewart as “delightful, compassionate, appreciative, kind, soft-spoken, and humble.”

Courtesy of Evelyn Floret

Author Margaret Atwood in her Toronto home with her cat Fluffy, 1989. “She was dazzling to me,” Floret said. “But I never felt intimidated by anyone I photographed. I just had this desire to do the best I could by them.”

Courtesy of Evelyn Floret

Harvey Fierstein with cast members of La Cage aux Folles, a show that he wrote, in 1984. He brought cast members to a studio at 18th and Broadway to be photographed. “That’s an example of the effort people made to give me a great photo,” Floret said.

Courtesy of Evelyn Floret

George Shearing, the blind jazz pianist, rode with his wife Ellie in Central Park, 1979. After the photo shoot Shearing sent Floret a thank you note written in Braille.

Courtesy of Evelyn Floret

Attorney Roy Cohn, 1984. For Evelyn Floret this was the rare case of her photographing an individual with a notorious reputation, and that influenced the resulting photo. “Having him in that setting seemed appropriate,” she said. “It was just like a mixed message. You could draw your own conclusions. Live animal and stuffed animal, animal that was made out of china.”

Courtesy of Evelyn Floret

Midori in 1981, at age 11. Later that year, at a New Year’s Eve concert, she would perform a solo with the New York Philharmonic. She went on to become a great performer and advocate for music education.

Courtesy of Evelyn Floret

Hugues de Montalembert was a painter who lost his sight after being attacked during a burglary in his New York apartment. He then turned to writing. Floret captured his spirit by photographing him riding a horse on a Long Island beach. Another horseman rode just out of view to guide De Montalambert along. Floret says, “I was nearly in tears while capturing this photo.”

Courtesy of Evelyn Floret

The post The Work of Evelyn Floret, a Master of Intimate Portraits appeared first on LIFE.

Studying MSc Analytical Science at RGU as an international student

RGU alumna Splendour shares her experience moving from Nigeria to Aberdeen to study a master’s in Analytical Science. She tells us about the highlights of her course, campus facilities, and how the degree has benefitted her. A little bit about me Hello, my name is […]

StudentRGU alumna Splendour shares her experience moving from Nigeria to Aberdeen to study a master’s in Analytical Science. She tells us about the highlights of her course, campus facilities, and how the degree has benefitted her.

A little bit about me

Hello, my name is Splendour, and I’m a proud graduate of RGU, with an MSc in Analytical Sciences, specialising in Food Analysis, Authenticity, and Safety.

My passion for scientific research, and the quality of food that we consume led me to pursue this degree. Studying at RGU has been a transformative experience, both academically and personally, and I’m excited to share my journey with you.

Choosing to study at RGU

When searching for a master’s programme, I wanted a course that combined practical laboratory experience with industry relevance. RGU stood out due to its strong emphasis on applied learning, state-of-the-art facilities, graduate employability, and close links to the industry.

My specialisation in Food Analysis, Authenticity, and Safety was based on my experience with food security and quality control in my home country. I have come to learn the importance of food safety, and sustainability in both Nigeria and globally.

Studying MSc Analytical Science at RGU

One of the most rewarding aspect of my time at RGU was the opportunity to engage in practical research. I had the privilege of working in advanced laboratories, with brilliant lecturers who were willing to help at any time. Furthermore, using cutting-edge techniques gave me real-world exposure to the challenges and innovations in the food industry.

Another standout experience was collaborating with peers from diverse backgrounds. My lab partners made my research work quite enjoyable. The exchange of ideas, perspectives, and experiences enriched my learning and broadened my global outlook on scientific research.

Living in Aberdeen and accessing RGU’s campus

Aberdeen provided a unique and welcoming environment for my studies. The supportive learning environment at RGU, combined with the city’s multicultural community, made adapting to life in Scotland enjoyable.

The RGU campus is truly inspiring. The riverside setting, easy bus transportation, cafes and lunch facilities where students often hang out with their friends, and the modern labs and libraries offer everything needed for academic success. One of my favourite places was the Sir Ian Wood Building, where I spent countless hours working on experiments and projects. The access to top-tier research facilities made a significant difference in my learning journey.

The takeaways from my experience at RGU

The MSc in Analytical Sciences has provided me with invaluable skills that are essential in my field. From laboratory techniques to industry standards and problem-solving, I feel well equipped to pursue a career in food analysis and quality assurance. The industry connections I made at RGU and the practical knowledge gained during my degree will undoubtedly open doors for future opportunities.

Beyond technical skills, this experience has also enhanced my confidence to communicate effectively, adaptability, and ability to work in diverse teams, which are vital qualities in any professional setting.

Studying at RGU has been one of the most rewarding experiences of my life. I made solid connections with my teachers, made friends, and learned life skills from another perspective. As I move forward in my career, I am grateful for the knowledge and experiences gained at RGU, and I look forward to applying them to make a meaningful impact in my field.

Splendour Otamiri

Related blogs

Studying a master’s in Analytical Science with RGU’s lab facilities

Studying a master’s in Analytical Science on RGU’s campus

The post Studying MSc Analytical Science at RGU as an international student appeared first on RGU Student Blog.

Working in AI as a Business graduate

RGU alumnus Mark has developed a successful career after graduating from BA (Hons) Management, taking on a variety of positions. Now leading a large team for an AI company, he shares how RGU helped him get to where he is now. Why did you choose […]

StudentRGU alumnus Mark has developed a successful career after graduating from BA (Hons) Management, taking on a variety of positions. Now leading a large team for an AI company, he shares how RGU helped him get to where he is now.

Why did you choose to study Business at RGU?

I chose to study Management at RGU because in truth, I had no real idea what I wanted to be when I grew up… and I think that may still be partially true now!

I did know that I found the business world fascinating, and that a flexible degree with many possible exit paths felt like it would give me a load of options once I had finished university, and that in some ways I could figure it out as I went along.

The Management degree at RGU gave me exactly the variety that I was seeking. The degree structure allowed me to learn, to a decent depth, about the core functions of any business – HR, Operations, Marketing, Legal, Finance, etc – without me feeling trapped in any way into having to enjoy or choose one over another at such an early stage in my life.

My career after graduation

Now, I am about 12 years into my career and have had the privilege of working in almost all of these functions for some of the biggest companies in the UK. The core principles of how to approach problem solving (and business is just problem solving!) that I learned from my degree have given me an incredible foundation from which to build on, and given me the springboard into learning a lot more as I have progressed in my career.

The job that I do now (leading a large, multi-continent team for an AI company) did not exist 12 years ago. However, I do think that the grounding, business understanding and the mental acuity that a Management degree from RGU offers, is as good a way as any to equip yourself for the jobs of the future.

And so whilst you also may not know what you want to be when you grow up, I’d consider that to be a strength from which you can build variety and flexibility into your studies and early years of your career, and Management or a similar degree from RGU is a great place to start.

Mark Meghezzi

Related blogs

Becoming a CEO and travelling the world after graduating from International Tourism Management

How studying Management with Marketing helped kickstart my career

The post Working in AI as a Business graduate appeared first on RGU Student Blog.

How We Conquered the RGU Hackathon: A 24-Hour Blitz of Innovation, Grit, and Game-Changing Connections!

The annual RGU Hack, led by the RGU Computing Society, is back on Saturday 22 February and Sunday 23 February with several leading sponsors. Previous Hackathon winner Rohith tell us how his team managed to come out on top and shares advice to those participating […]

StudentThe annual RGU Hack, led by the RGU Computing Society, is back on Saturday 22 February and Sunday 23 February with several leading sponsors. Previous Hackathon winner Rohith tell us how his team managed to come out on top and shares advice to those participating this year to make the most of the opportunity.

We were a ragtag crew of four—three technical newbies and one nontechnical dynamo—ready to disrupt the status quo at the RGU Hackathon. With zero experience in machine learning but a hunger to push our limits, we dove headfirst into one of the toughest challenges on the menu. And guess what? We came out on top!

The Challenge: Embrace the Unknown!

Walking into the hackathon, we had no roadmap. Competing against fierce teams from Glasgow, Edinburgh, and beyond, the energy in the room was electric. Our mantra was simple: win at any cost!

Every moment was a high-stakes sprint, and we were all in—fueled by determination and raw ambition.

Teamwork under pressure

Diverse skills, one mission: We may have been newbies, but our mix of fresh perspectives turned obstacles into opportunities.

Communication is King: Clear, rapid-fire communication kept us in sync and laser-focused on our goal.

Smart commitments: Overcommitting kills momentum. We aimed to commit less and deliver more—every single hour counted!

Survival essentials for the win

Hackathons aren’t just about brainpower; they’re a test of endurance, so:

Pack the Basics: Laptop charger? Check. Mobile charger? Check. Snacks and drinks are covered by RGU.

Stay Comfortable: You get to chill and relax and work anywhere inside the University but, bring a pillow, water bottle, and even a bedsheet. (Yes, the campus is warm, but comfort fuels creativity!)

Camp It Out: The hack wraps up at noon, with winners announced after the demo. Stay on campus to catch every electrifying moment.

Networking: The ultimate hack

Employees from companies will be hanging out with you for a short bit, and it’s always a good idea to get more perspective of the problem they want solution for. Give them what they need and beyond. Beyond the code, the hackathon is a goldmine for connections:

Team Up Early: Don’t just stick with familiar faces. Seek out new teammates—diversity breeds innovation!

Pizza & Drinks Breaks: Every four hours, you will have a break. While waiting in a queue, take the chance to connect and transform the down time into an epic brainstorming session. Chat over pizza, share ideas, and build relationships that could be your ticket to future opportunities.

Industry Insider Access: Rub elbows with top professionals from leading Aberdeen companies. These connections are not just chance meetings—they can pave the way to your dream career.

Grit, Grind, and a Dash of Guts

Our hackathon journey was a whirlwind:

Mindset of a Champion: The singular focus was victory—win at any cost. Every line of code, every late-night brainstorm, and every caffeine-fueled minute was dedicated to crushing the competition.

Learning on the Fly: Even with early-stage, clunky versions of ChatGPT (think slow and

clumsy code engine), we learned to adapt and innovate. Every challenge was a stepping stone toward our win.

Final Takeaways for Aspiring Hackers

Embrace the Challenge: Don’t fear the unknown. Tackling a tough project head-on sparks the most innovative solutions.

Work Smart, Not Just Hard: Prioritise quality over quantity. Commit strategically, and always deliver more than you promise.

Network Like a Pro: Use every break, every conversation, as an opportunity. These moments might just open doors to your future.

Conclusion

Winning the RGU Hackathon wasn’t just a triumph—it was an adrenaline-fueled lesson in teamwork, resilience, and the power of daring to dream big. This opened me up to an opportunity for an interview with the company. For all the first-timers and aspiring hackers out there: gear up, prepare with passion, and let your ambition lead the way. Your next breakthrough—and perhaps your future career—starts with taking that bold leap!

Rohith Ajith

Related blogs

Coding, teamwork, and a winning project: my RGU Hack experience

Taking part in the Inform Prize Competition with my computing team

The post How We Conquered the RGU Hackathon: A 24-Hour Blitz of Innovation, Grit, and Game-Changing Connections! appeared first on RGU Student Blog.

Ella Fitzgerald: The First Lady of Song

Ella Fitzgerald has been described as “perhaps the quintessential jazz singer.” This live performance of “Let’s Do It (Let’s Fall In Love)” is one of the countless examples of Ella Fitzgerald thrilling an audience with her talents. In 1955 LIFE’s Eliot Elisofon photographed Fitzgerald for […]

PeopleElla Fitzgerald has been described as “perhaps the quintessential jazz singer.” This live performance of “Let’s Do It (Let’s Fall In Love)” is one of the countless examples of Ella Fitzgerald thrilling an audience with her talents.

In 1955 LIFE’s Eliot Elisofon photographed Fitzgerald for a story on the top jazz stars of the day, and she was the only woman included in the group. LIFE wrote of her, “Ella Fitzgerald, who sings love ballads daintily, can roar on like a trombone through a jazz classic. Her most famous number is “A-Tisket, A-Tasket,” but it is her many hotter songs that keep her the first lady of jazz year after year.”

In 1958 LIFE staff photographer Yale Joel took his turn shooting Fitzgerald. He caught her performing at Mister Kelly’s, a renowned jazz club in Chicago. The photo places the viewer in a front row seat. Fitzgerald, elegantly dressed, sings with her eyes closed and hand to heart on a low stage that has her nearly at level with the audience. That photo is one of the most popular images in LIFE’s print store, which is a tribute to both Joel’s skill and Fitzgerald’s enduring popularity—several of her songs have more than 100 million plays on Spotify.

Included here are several other of Joel’s shots from Mister Kelly’s, and also other instances in which LIFE’s photographers documented this great artist.

Singer Ella Fitzgerald holding a basket of flowers as she sings A-Tisket, A-Tasket in front of backdrop, 1946.

Eliot Eilsofon/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Jazz singer Ella Fitzgerald performed at Mister Kelly’s nightclub in Chicago, 1958.

Yale Joel/Life PIcture Collection/Shutterstock

Bathed in red light, American jazz singer Ella Fitzgerald performed her eyes closed, at Mister Kelly’s nightclub, Chicago, 1958.

Yale Joel/Life PIcture Collection/Shutterstock

Ella Fitzgerald performed at Mister Kelly’s nightclub in Chicago, 1958.

Yale Joel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Ella Fitzgerald performing at Mister Kelly’s nightclub in Chicago, 1958.

Yale Joel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Ella Fitzgerald mingled with people who had come to hear her perform at the opening night of the Bop City nightclub in New York City, April 1949.

.Martha Holmes/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Songbird Ella Fitzgerald sang at opening at the Bop City nightclub in New York City, 1949.

Martha Holmes/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Ella Fitzgerald sang during opening night of Bop City nightclub in New York City, April 1949.

Martha Holmes/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Ella Fitzgerald at the old Madison Square Garden in New York on the night Marilyn sang to John F. Kennedy, May 1962.

Bill Ray/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Ella Fitzgerald, the Queen of Jazz, 1954.

Eliot Elisofon/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

The post Ella Fitzgerald: The First Lady of Song appeared first on LIFE.

Studying midwifery at RGU

Third-year midwifery student Emma shares her experience of the course and placements, and how she has been supported with her dyslexia and dysgraphia at RGU. How I enrolled at RGU I’m Emma, and I’m currently a third-year student midwife at RGU. From a young age, […]

StudentThird-year midwifery student Emma shares her experience of the course and placements, and how she has been supported with her dyslexia and dysgraphia at RGU.

How I enrolled at RGU

I’m Emma, and I’m currently a third-year student midwife at RGU.

From a young age, I knew I always wanted to care for and look after people. It was a toss-up between cancer nursing and midwifery for me. However, midwifery just stuck; everyone knew I was focused on becoming a midwife.

I attended the RGU Open Day with my family, and I got to speak with the lecturers and 3rd-year students. This really solidified that I wanted to attend RGU as I could see myself thriving there. So, I was absolutely delighted when I got my offer.

Recently, I had a full circle moment as I was the third year that was helping with the open days, talking to the applicants and showing me how far I had come from being there myself.

My experience with Midwifery at RGU

I feel like my time studying midwifery at RGU has gone by extremely fast, but it’s been so enjoyable. The staff have been so supportive, as this course is intense at times. I would encourage the use of personal tutors, Study Skills and the Inclusion Centre as they have been amazing through my official diagnosis of dyslexia and dysgraphia, putting in place reasonable adjustments in theory modules and placement.

Placements at first were daunting. However, you slowly get into the swing of things, consolidate your learning and pick up tips from each midwife. A massive highlight is being there for women and their families on such a special journey. It will always be such a privilege for me to be a part of this.

The team was so supportive when I was nervous about switching health boards for my placement in 2nd year from NHS Grampian to NHS Tayside. I was excited to be home for placement but anxious to have to re-learn some things and find my way around a new hospital. However, my personal tutor showed me around Ninewells to get my bearings and help with the stress of where I was to go, and I got to meet the lovely staff that was on shift that day, putting me at ease.

I was also lucky enough to be selected for the interprofessional learning day with the 4/5th year medical students from Aberdeen University running through simulations of obstetric emergencies. It was fun running through these scenarios seeing how far I had come from first year.

My aspirations after graduation

I hope to become a midwife either in the wards or in the labour suite as I enjoy building relationships with women over multiple shifts and how rewarding each shift makes you feel like you have made a difference.

Emma Todd

Related blogs

Pursuing my dream of becoming a midwife as a mum of four

Studying midwifery in Scotland

The post Studying midwifery at RGU appeared first on RGU Student Blog.

The Strangest College Class Ever

Picking out the oddest offerings from the wide world of academia has become something of a modern pastime. Lists of such courses abound online, including this one from U.S. News and World Report that includes such headscratchers as “Paintball Kinesiology” and “DJing and Turntablism.” I […]

LifestylePicking out the oddest offerings from the wide world of academia has become something of a modern pastime. Lists of such courses abound online, including this one from U.S. News and World Report that includes such headscratchers as “Paintball Kinesiology” and “DJing and Turntablism.”

I mean, what happened to studying Plato, right?

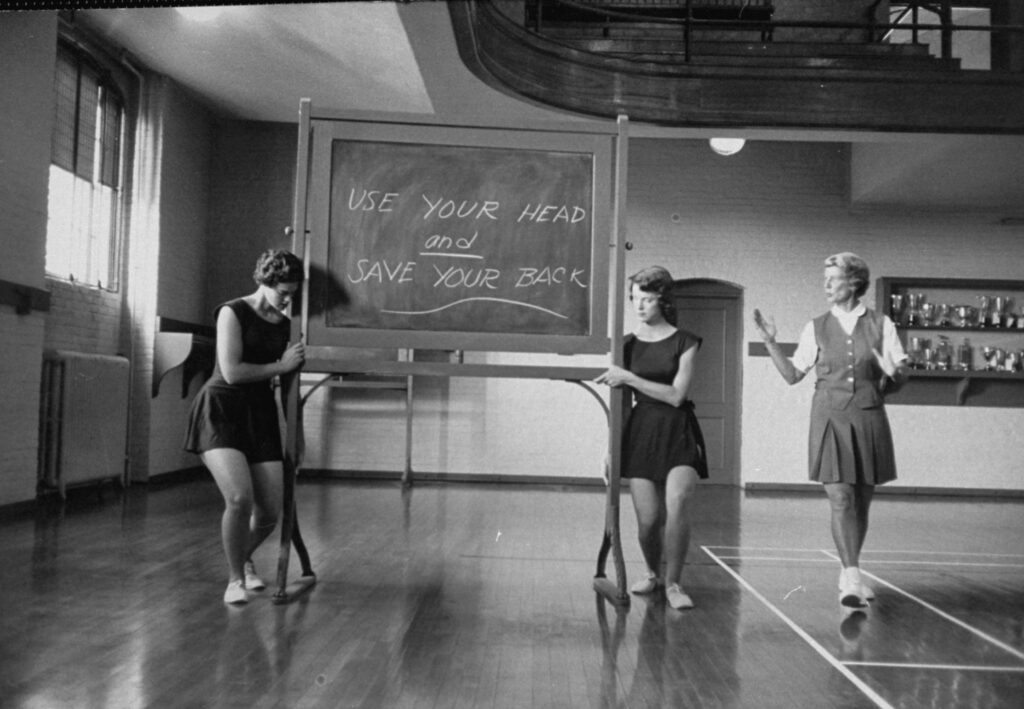

In 1958 LIFE magazine was early to the party with its story about a class being offered at Smith College, the highly respected all-female school in Northampton, Massachusetts. The headline: “College Class in Luggage Lifting.”

That headline, like many of today’s online lists, was meant to provoke a reaction. Smith College wasn’t exactly offering a full-blown course in the proper way to lift a bag, but luggage handling was a real addition of the college’s physical education curriculum.

The LIFE story explained why Smith was suddenly concerned about its students handling luggage the right way:

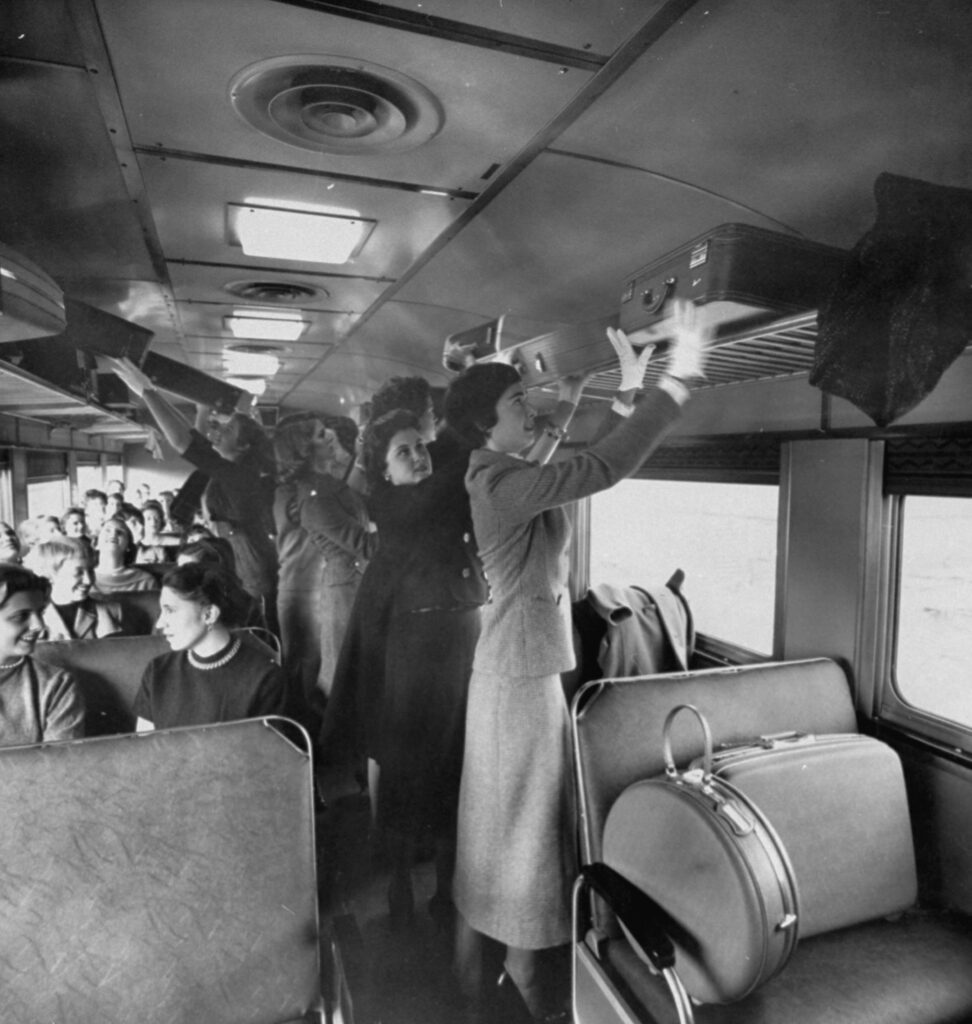

For years Smith’s physical education department has been teaching posture to its freshman. But when redcap porter service was cut back at the nearby railway stations, the college found that the girls were displaying un-Smithlike sags and sways as they struggled with their suitcases. To preserve both appearances and backs, the college added baggage handling to the course.

Perhaps the most interest aspect of this story, viewed all these years later, is the idea of what “un-Smithlike” behavior constituted in the 1950s. The course also created an irresistible photo opportunity that LIFE sent staff photographer Yale Joel to capitalize on. He took photos in both the gym class itself, and of students applying their knowledge in an out-of-use car of the Boston and Maine Railroad.

The conclusion of the LIFE story is very much of its time, which was a decade before the women’s liberation movement began to hit its stride. One freshman dismissed the need for a baggage-handling course by saying, “A girl who tries can almost always find some man to help her with her luggage.”

Assistant professor Anne Delano led a class on physical education that included instruction on handling luggage, with the motto “Use Your Head and Save Your Back” written out on a chalkboard, 1958.

Yale Joel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Improving back flexibility was part of the physical education program at Smith College designed to make students better able to handle their own luggage, 1958.

Yale Joel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Smith College college practiced the proper method for lifting luggage with bags that contained 12-pound weights, 1958.

Yale Joel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Smith College college practiced the proper method for lifting luggage with bags that contained 12-pound weights, 1958.

Yale Joel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Smith College students posed for a photo for a story about them being taught the best way to handle a suitcase, 1958.

Yale Joel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Undergraduates at Smith College practiced the proper method for handling luggage, a skill they were taught as part of the school’s physical education program, 1958.

Yale Joel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Smith College girls received instruction in the proper way to handle suitcases after redcap service was removed from local train stations, 1958.

Yale Joel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Smith College girls received instruction in the proper way to handle suitcases after redcap service was removed from local train stations, 1958.

Yale Joel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

The post The Strangest College Class Ever appeared first on LIFE.

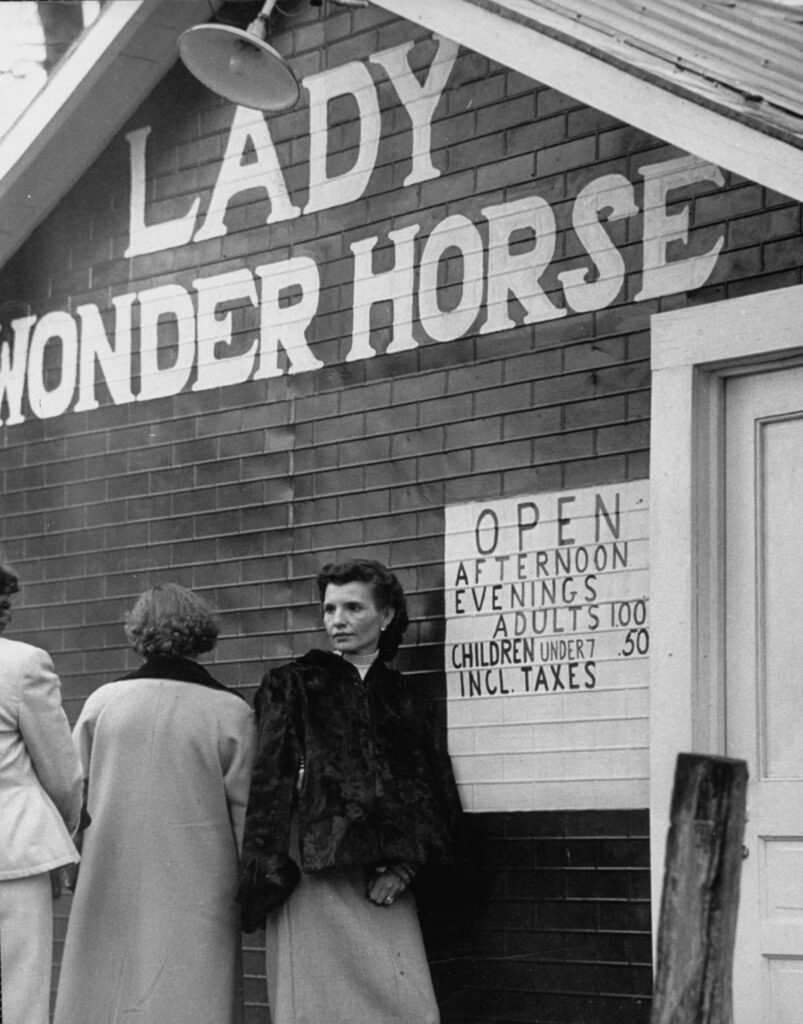

Meet Lady Wonder, the Psychic Horse Who Appeared Twice in LIFE

The story of Lady Wonder began in 1925, when her owner, Mrs. Claudia Fonda of Richmond, Va., noticed that the horse she had purchased when it was two weeks old—then just called Lady— would come when Fonda was merely thinking of calling her. Fonda wondered […]

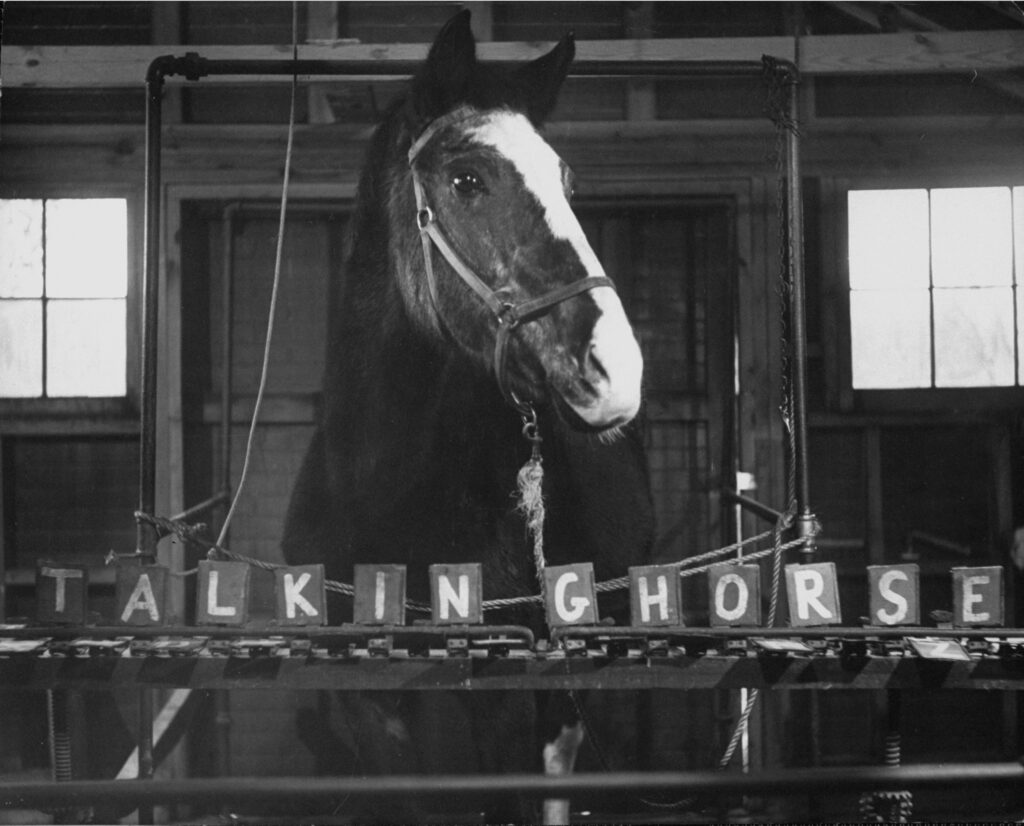

AnimalsThe story of Lady Wonder began in 1925, when her owner, Mrs. Claudia Fonda of Richmond, Va., noticed that the horse she had purchased when it was two weeks old—then just called Lady— would come when Fonda was merely thinking of calling her. Fonda wondered if the horse could read her mind, she told LIFE. By the time Lady was two years old the horse had been taught to spell out words by using blocks with letters on them. When Lady correctly predicted the winner of the Dempsey-Tunney boxing match, the fame of what Fonda billed as “The Mind-Reading Horse” began to spread.

Lady Wonder’s first appearance in LIFE came in 1940, when the magazine, as part of a larger story on ESP, related the history of the horse but also reported that it had lost its extra-sensory special powers. The horse could still perform simple mathematics, though, and was at that point merely being billed as “The Educated Horse,” with claims of clairvoyance left by the wayside. Still, the story noted that its ESP expert believed the horse once posessed special powers.

Then in 1952 Lady Wonder returned to the spotlight when she seemingly offered insight to a tragic case involving a missing boy. Here’s how LIFE described her contribution in its issue of Dec. 22, 1952:

A friend of the district attorney of Norfolk County, Mass., went to see her, on a hunch, to ask her for news of a little boy who had been missing for months. She answered, “Pittsford Water Wheel.” A police captain figured out that this was a psychic misprint for “Field and Wilde Water Pit,” an abandoned quarry. Sure enough, that is where the boy’s body was found.

The incident brought national attention to Lady Wonder, and among those who made the pilgrimage to her Virginia farm was LIFE photographer Hank Walker. He captured the mare, then 27 years old, in action, dispensing advice and sports predictions. (For the specific college football picks from Lady Wonder mentioned in the article, the horse was right on only one out of three picks).

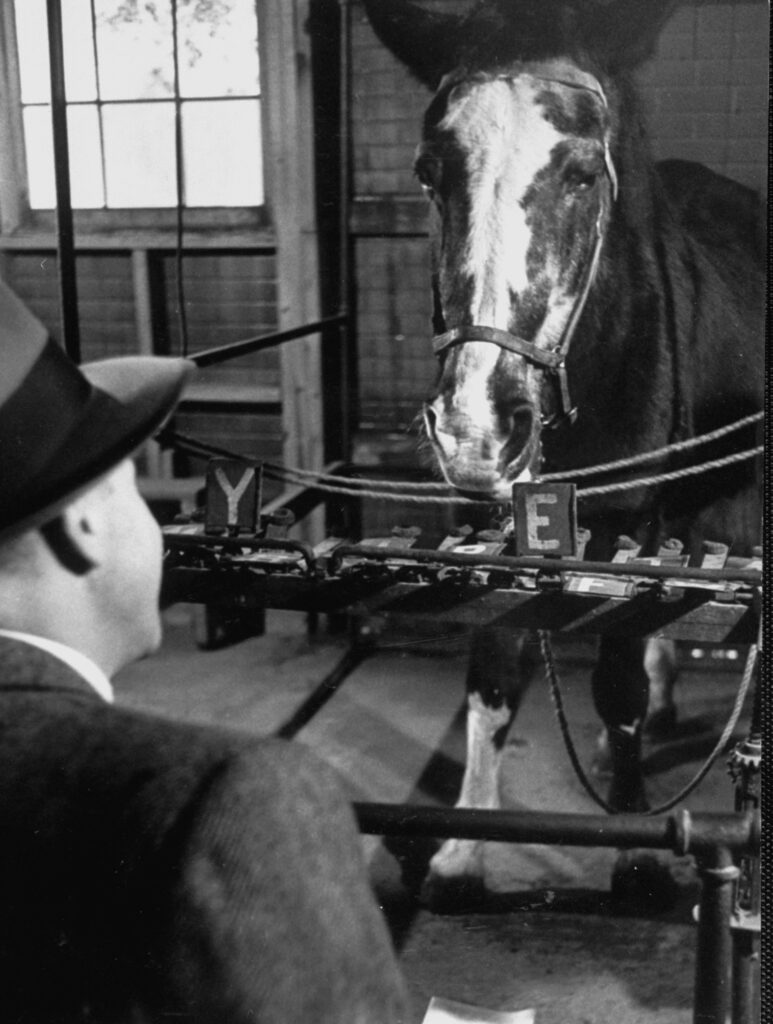

Not everyone was buying the act. In 1956 the magician Milbourne Christopher, who was a noted debunker of frauds, visited Lady Wonder’s stable and concluded that the horse was spelling out words under the subtle guidance of Fonda, who was directing Lady Wonder on which blocks to select.

Lady Wonder died the next year.

The 27-year-old Lady Wonder, a horse with purported clairvoyant abilities who communicated answers by flipping letters on a rack, was a popular tourist attraction in Richmond, Va,. 1952.

Hank Walker/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

The 27-year-old Lady Wonder, a horse with purported clairvoyant abilities who communicated answers by flipping letters on a rack, was a popular tourist attraction in Richmond, Va,. 1952.

Hank Walker/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

The 27-year-old Lady Wonder, a horse with purported clairvoyant abilities who communicated answers by flipping letters on a rack, was a popular tourist attraction in Richmond, Va,. 1952.

Hank Walker/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

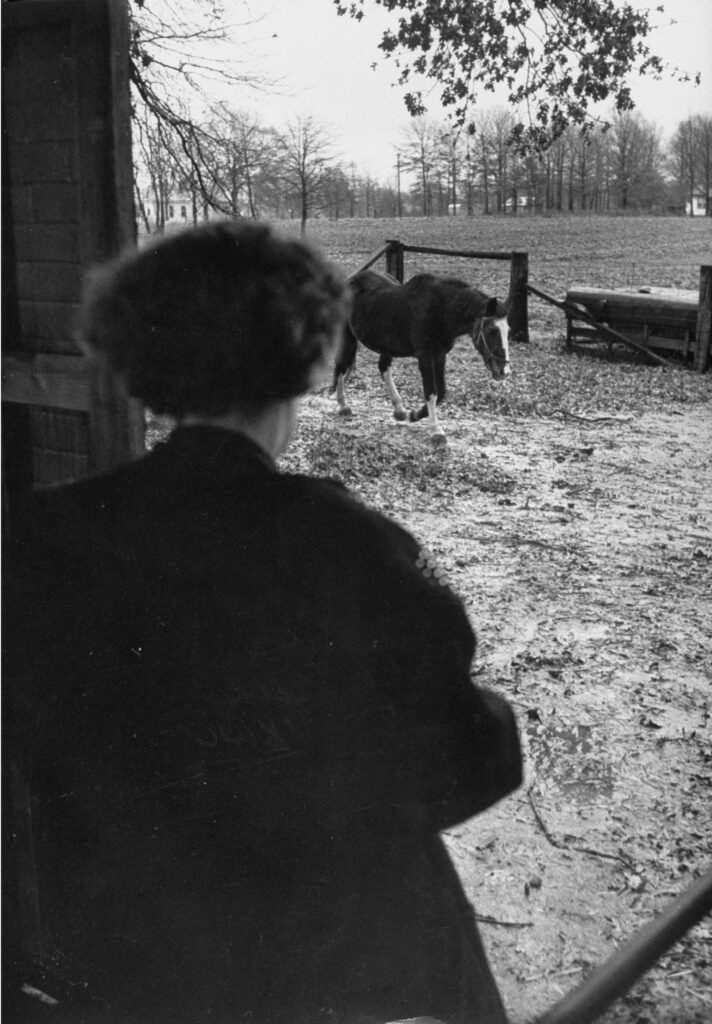

“Lady Wonder,” a horse with the purported ability to see the future, came in from the pasture to answer questions for her customers, Richmond, Va., 1952.

Hank Walker/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

The 27-year-old Lady Wonder, a horse with purported clairvoyant abilities who communicated answers by flipping letters on a rack, was a popular tourist attraction in Richmond, Va,. 1952.

Hank Walker/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Mrs. Julius Bokkon regularly visited Lady Wonder to solicit the opinion of the clairvoyant horse on matters in her life, Richmond, Va., 1952.

Hank Walker/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Lady Wonder, the purported clairvoyant horse, gave a Massachusetts businessman direction on where to get a loan, spelling out “Heancock,” which was interpreted to mean the insurance company John Hancock, 1952.

Hank Walker/LIfe PIcture Collection/Shutterstock

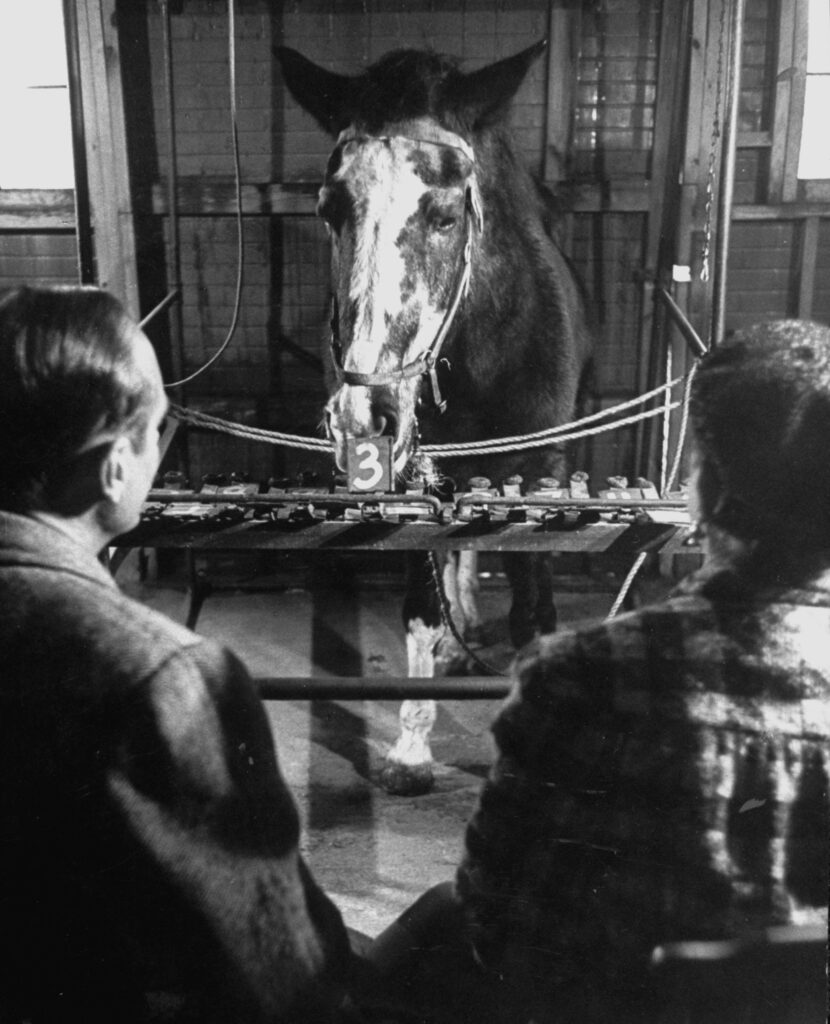

The tricks of Lady Wonder included performing addition; here she had been asked what 7+6 equalled (she had already pulled up a “1” that is out of view to the left), Richmond, Va., 1952.

Hank Walker/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Owner Claudia Fonda stood by as her clairvoyant talking horse tourist attraction, Lady Wonder, gave a Massachusetts businessman direction on where to get a loan, spelling out “Heancock,” which was interpreted to mean the insurance company John Hancock, 1952.

Hank Walker/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

The 27-year-old Lady Wonder, a horse with purported clairvoyant abilities who communicated answers by flipping letters on a rack, was a popular tourist attraction in Richmond, Va,. 1952.

Hank Walker/LIfe PIcture Collection/Shutterstock

Lady Wonder, a horse with supposed clairvoyant powers, attracted visits from tourists and well as regulars such as Mrs. Julius Bokkon, Richmond, Va., 1952. The levers around the horse were like keys in a giant typewriter that it used to communicate its messages.

Hank Walker/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

The post Meet Lady Wonder, the Psychic Horse Who Appeared Twice in LIFE appeared first on LIFE.